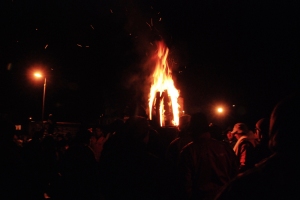

The Burning of the Clavie on January 11 in Burghead marks the start of the new year – it’s the old date of New Year’s Eve, Hogmanay, before the change to the Gregorian calendar in 1752. The barrel filled with tar and pieces of wood, and specially shaped for being carried by a single bearer, is taken round the village by the Clavie king and the Clavie crew, and then set up on the Doorie Hill for its fiery end. The embers are given to the various households to bring good luck for the new year ahead.

Burghead is also notable for the images of a bull which were found when the harbour of today was built in 1805. The bulls are inscribed in Pictish style, and are the only such bulls from that period to be found in Scotland. There are inscriptions of bovine animals at other sites, but they are cows. Around 30 of the bulls were found when the present-day fishing harbour of Burghead was developed, two centuries ago, and today only six remain, four locally in Burghead and Elgin, one in Edinburgh, and one in the British Museum.

There are stories of bulls being sacrificed in one or two other parts of the Highlands of Scotland on special occasions, and from the Western Isles a tradition of someone dressed in the hide of a bull going round at Hogmanay. At each house he would singe his tail at the hearth fire and hold it out for each member of the household to sniff, for good luck for the coming year.

And around 25 miles to the south of Burghead, at Inveravon, the Kirk Session records for 1714 reveal ‘ane act against clavies’, and Marian McNeill, who quotes the story, suggests that the word ‘clavie’ may come from the Gaelic cliabh, meaning a basket.

However, given that the New Year traditions for Scotland are generally strong, mentions of a bull and an association with fire are really only found in fragments. These fragments are so few that they may not necessarily be the remnants of an ancient custom across the whole country; they could also be something local that has happened to spread to one or two other areas.

The bull in the sky

There is however an example of a tradition of a bull and the journey of torchbearers which could have reached Burghead around eighteen hundred years ago; this is the Roman cult of Mithras.

The classic analysis of the cult has been carried out in recent years by Prof. David Ulansey in books such as The Origin of the Mithraic Mysteries and articles in journals including Scientific American. David Ulansey is Professor Emeritus of Philosophy and Religion at the California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco, and specialises in the religions snd cosmologies of the ancient Mediterranean world.

The Mithras cult, which reached its peak in the 3rd century AD, involved activities in an underground temple, meant to replicate the underground cave where it was said that the god Mithras killed a bull. The cult was particularly popular amongst soldiers, and it had administrators and merchants as well. The greatest concentrations of Mithraic temples are found in Rome itself, and also notably in those parts of the Empire – often on the most distant frontiers – where Roman soldiers were stationed.

Previously the cult had been regarded as coming from Iran, and the ancient god Mithra. However, there are no accounts in Iranian mythology of Mithra killing a bull. David Ulansey looked instead at the pictures of Mithras killing the bull – and how there would be particular other animals in the images, four in all – a dog, a snake, a raven, and a scorpion. Dog, snake and scorpion are beautifully shown in this picture from the Vatican Museums taken by Canadian photographer Gregory Melle.

David Ulansey noted a point made by two earlier scholars (the German K.B. Stark and the Canadian Roger Beck): that the Mithraic scenes are pervaded by astronomical imagery – the zodiac, planets, sun, moon and stars. So suppose, he said, that this whole cult is about astronomy; that the bull at the heart of it is the constellation Taurus; that the dog is Canis Major, the snake Hydra, the raven Corvus, and the scorpion Scorpio. All five constellations are located in a continuous band in the sky.

What then is the significance of the core image, the death of the bull? Ulansey says that this refers to the precession of the equinoxes, whereby the direction of the axis of the earth’s rotation slowly changes over a period of approximately 26,000 years. This wobble means that the polar point in the sky, the axial point about which the whole sky seems to turn, changes very slowly over time. This polar point today coincides with the location of the star Polaris, and indeed gives the star its name. In the past its location was slightly different, and over a period of around 26,000 years it will describe a little circle in the sky.

When we look up at the night sky, we see the stars turning around the fixed axial point, a bit like a giant mill, with the band around the mill – the celestial equator – holding the great structure together. There is a second band in the sky, formed by the earth’s orbit around the sun. As the year progresses, the rising-place of the sun makes a journey through the sky, its course going through the zodiac.

The two bands are bound together, meeting at two points – the spring and the autumn equinoxes. They mark the times of balance, when the sun’s journey through the constellation of the zodiac crosses the band in the sky formed by the earth’s rotation. We might think of these two crossing-points as riveting the framework that holds the universe together.

The wobble in the direction of the earth’s axis means a very slow and gradual move of the band of the celestial equator, and hence a very slow and gradual change in the crossing-points of the celestial equator with the zodiac – and this is the precession of the equinoxes.

The spring equinox today is in the constellation of Aquarius – hence the song about the dawning of the Age of Aquarius. For the previous two thousand years or so, it was in the constellation of Pisces, the Fish. For two thousand years or so before that, from around 2000 BC onwards, it was in Aries the Ram. And for two thousand years or so further back, it was in Taurus the Bull.

The journey of the torchbearer

Now in the year 128 BC, the Greek astronomer Hipparchus is said to have discovered the precession of the equinoxes. There are reasons for thinking that this was in fact a rediscovery, in that the phenomenon was known in more ancient times, but what matters in the present context is that the concept came to the fore in the 1st century BC. The discovery of powerful forces of change in the heavens had huge significance for people on the earth below, since the sky was regarded as the place where the human soul journeys after death.

‘A new force had been detected capable of shifting the cosmic sphere,’ he says. ‘Was it not likely that this new force was a sign of the activity of a new god, a god so powerful that he was capable of moving the entire universe?’

It is this god, given the name of Mithras, who was seen to have taken the spring equinox away from the Bull – and hence to have overcome his great power: to have slain him.

And that, says Ulansey, was exactly the way in which the worshippers of Mithras regarded him. One example is a scene showing the young Mithras holding a sphere in one hand and rotating a circle with the other – this will be the circle of the zodiac.

There is also an image of Mithras in the role of the god Atlas, supporting the world on his shoulder, as Atlas traditionally does.

And there is one more aspect of Mithras that is worth noting. There are a number of scenes of his birth, in which he is said to have sprung to life out of a rock. In almost all of these scenes, he is shown as carrying a torch.

Two torchbearers were part of the Mithras ritual. A bull was killed in an underground pit, and two attendants held flaming torches, one turned up and the other pointing down.

What does the torch represent? In the ancient world, the sun was often depicted as a torchbearer, and one of the ancient Greek cults includes a torchbearer who is said to be the sun. David Ulansey suggests that the torch pointing up is the spring equinox in Taurus the Bull, and the torch pointing down is the autumn equinox in Scorpio.

So a torchbearer travelling round a fixed route is to the fore in the Mithras cult – associated with a bull and the passage of the seasons.

But how could a Mithras cult from Rome have ever reached Burghead? That is what we will look at in the second part of this story.

The Mithras monument is CIMRM 548 in Vermaseren’s catalogue of Mithraic monuments.

Many thanks for this link, and I do apologise for the long delay in replying – I had copied material to another site and not checked here for some time, and indeed with the very interesting comments that have come in I’m going to continue the discussion here and add further material.

This map shows the main features of the Burghead bull as relating to the slabs of stone.

If you look at Suenos stone in Forres it seems to be a map of the landscape east of Forres -click on compressed zipped folder.

I think most pictish and ancient stones are maps of the local area. At carnwath near Lanark there is a stone with triangles on it.

The river clyde has very sharp triangular bends on it at carnwath. The tuning fork on a stone near Perth is symbolic of where an island in the river Tay splits the river in two.

regards

Alistair

________________________________

The eye of the Burghead bull is Burghead well and the horn is the burghead promontory.

The curved shape of the bull is the outline of the coast and the curved tail is a river west of burghead.

This is fascinating, and I do apologise for not replying sooner to your earlier comments. I had copied some of the material on the site to another site, but indeed there are so many interesting comments on this site that I am going to continue it.

That is most interesting what you say about the bull being on the ground at Burghead. In various places there seem to be constellations laid out on the ground, sometimes one (like Orion), and sometimes more.

The well, as the eye of the bull, would then be in a key position.

It would be interesting o see a diagram of this.

The romans noted 18.5 hours daylight at burghead in midsummer and this is close to 18.6 which is the time in years of the lunar metonic cycle.

That’s interesting, and that figure makes me wonder if Burghead could have been significant in the pre-Roman period for astronomy?

My uncle found a spiral ditch 60 feet across in the woods close to Alves at the same longitude as burghead.

That would be most interesting to hear more about.